ââ⢠on the Issues Magazine Miniretrospective of the Art of Miriam Schapiro Linda Stein

| Miriam Schapiro | |

|---|---|

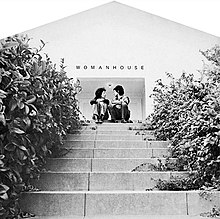

Front folio of the exhibition catalog for Womanhouse, photograph by Sheila Levrant de Bretteville | |

| Born | Nov 15, 1923 Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Died | June 20, 2015(2015-06-20) (anile 91) Hampton Bays, New York, U.s.a. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | BA, University of Iowa (1945), MA, University of Iowa (1946), MFA, University of Iowa (1949) |

| Known for | Painting, Printmaking, Collage, Femmage, |

| Motion | Abstruse Expressionism, Feminist art, Pattern and Ornament |

| Spouse(s) | Paul Brach |

| Awards | College Art Association Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Accomplishment (2002) |

Miriam Schapiro (also known every bit Mimi) (November 15, 1923 – June 20, 2015) was a Canadian-born artist based in the Usa. She was a painter, sculptor, printmaker, and a pioneer of feminist art. She was too considered a leader of the Design and Ornament art move.[i] Schapiro'south artwork blurs the line betwixt fine art and craft. She incorporated craft elements into her paintings due to their clan with women and femininity. Schapiro's work touches on the issue of feminism and art: especially in the aspect of feminism in relation to abstract fine art. Schapiro honed in her domesticated craft work and was able to create work that stood amongst the remainder of the high art. These works correspond Schapiro's identity every bit an creative person working in the center of contemporary abstraction and simultaneously every bit a feminist being challenged to represent women's "consciousness" through imagery.[two] She often used icons that are associated with women, such as hearts, floral decorations, geometric patterns, and the colour pink. In the 1970s she made the hand fan, a typically minor woman'due south object, heroic by painting it six anxiety by twelve feet.[iii] "The fan-shaped canvas, a powerful icon, gave Schapiro the opportunity to experiment … Out of this emerged a surface of textured coloristic complication and opulence that formed the basis of her new personal style. The kimono, fans, houses, and hearts were the course into which she repeatedly poured her feelings and desires, her anxieties, and hopes".[2]

Early life and education [edit]

Schapiro was born in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.[four] She was the but child of Russian Jewish parents. Her Russian immigrant granddaddy invented the first movable doll'south eye in the United States[5] and manufactured "Teddy Bears."[6] Schapiro later on included dolls in her work, as newspaper cutouts and every bit photo reproductions of images from magazines, and in her statement accompanying an exhibition of her work at the Flomenhaft Gallery, she remarked that "In our state nosotros don't feel about dolls as Europeans, Africans or Asians do," providing an anecdote that nuns at a Japanese temple explained their reason for beingness there was to intendance for the souls of the dolls.[7] Her father, Theodore Schapiro, was an creative person and an intellectual who was studying at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design, in New York, when Schapiro was born. He was an industrial pattern artist who fostered her desire to be an artist and served as her office model and mentor. Her female parent, Fannie Cohen,a homemaker and a Zionist, encouraged Schapiro to accept up a career in the arts. At age 6, Schapiro began cartoon.[8]

Every bit a teenager, Schapiro was taught past Victor d' Amico, her outset modernist instructor at the Museum of Modern Art.[9] In the evenings she joined WPA classes for adults to study cartoon from the nude model. In 1943, Schapiro entered Hunter College in New York City, but eventually transferred to the Academy of Iowa. At the Academy of Iowa, Schapiro studied painting with Stuart Edie and James Lechay. She studied printmaking under Mauricio Lasansky and was his personal banana, which then led her to help course the Iowa Impress Grouping.[2] Lasanky taught his students to use several different printing techniques in their work and to report the masters' work in order to find solutions to technical bug.

At the State University of Iowa she met the artist Paul Brach, whom she married in 1946.[4] After Brach and Schapiro graduated in 1949, Brach received a chore in the Academy of Missouri as a painting instructor. Schapiro did not receive a position, and was very unhappy during their time there. By 1951 they moved to New York City and befriended many of the Abstract expressionist artists of the New York School, including Joan Mitchell, Larry Rivers, Knox Martin and Michael Goldberg. Schapiro and Brach lived in New York City during the 1950s and 1960s. Miriam and Paul had a son, Peter Brach, in 1955. Before and after the birth of her son Peter, Schapiro struggled with her identity and place as an artist. Miriam's Schapiro's successive studios, after this period of crunch, became both environments for and reflections of the changes in her life and art.[ii]

She died on June xx, 2015 in Hampton Bays, New York, aged 91.[10] [11]

Career [edit]

Miriam Schapiro's art career spanned over 4 decades. She was involved in Abstract expressionism, Minimalism, Calculator art, and Feminist art. She worked with collage, printmaking, painting, femmage – using women's craft in her artwork, and sculpture. Schapiro not only honored the craft tradition in women's art, but also paid homage to women artists of the past. In the early 1970s she made paintings and collages which included photo reproductions of past artists such as Mary Cassatt. In the mid 1980s she painted portraits of Frida Kahlo on top of her onetime self-portrait paintings. In the 1990s Schapiro began to include women of the Russian Avant Garde in her work. The Russian Avant Garde was an important moment in Modern Art history for Schapiro to reflect on because women were seen as equals.[12]

New York and Abstract Expressionism [edit]

Paul Brach and Miriam Schapiro moved back to New York afterwards graduate school in the early 1950s.[9] Although Brach frequented The Gild where abstruse expressionist artists met to debate, talk, drink, and trip the light fantastic toe, she was never a fellow member. In 1 of her journals, she wrote that women were not viewed as serious artists by members of The Club.[xiii] Schapiro worked in the style of Abstract expressionism during this time period.

Between 1953 and 1957, Schapiro created a substantial body of work. Schapiro created her own gestural linguistic communication: "painting thinly and wiping out", in which the wiped surface area played a meaning role as the painted expanse. Although these works were abstracted such every bit her work Animate being State and Plenty, Schapiro based them off of black and white illustrations of works by the "old masters". In December 1957, André Emmerich selected one of her paintings for the opening of his gallery.[2]

Beginning in 1960 Schapiro began to eliminate abstract expressionist brushwork from her paintings and in order to introduce a multifariousness of geometric forms.[5] Schapiro started looking for maternal symbols to unify her ain roles as a woman. Her serial, Shrines was created in 1961–63 with this in mind. Information technology is 1 of her earliest group of work that was also an autobiography. Each section of the work show an aspect of beingness a adult female artist. They are also symbolic of her body and soul. The play betwixt the illusion of depth and the acceptance of the surface became the primary formal strategy of Miriam's piece of work for the rest of the decade.[14] The Shrines enabled Schapiro to discover the multiple and fragmented aspects of herself.[two]

In 1964 Schapiro and her husband Paul both worked at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop. I of Schapiro's biggest turning points in her fine art career was working at the workshop and experimenting with Josef Albers' Color-Aid paper, where she began making several new shrines and created her start collages.[14]

California [edit]

Figurer Art [edit]

In 1967, Schapiro and Brach moved to California and so that both could teach in the art department at the University of California, San Diego. In that location Schapiro met David Nalibof, a physicist who worked for Full general Dynamics. Nalibof formulated figurer programs that could plot and alter Miriam Schapiro's drawings. This was how one of her most iconic works, Big Ox #1 from 1968 was created. The diagonals of which represented the limbs of the "Vitruvian man," while the O depicted the center of the women, the vagina, the womb. This work is described as "a newly invented, trunk-based, archetypal emblem for female person power and identity, realized in bright red-orange, silver, and 'tender shades of pinkish'".[15] The O is besides thought to symbolize the egg, which exists every bit the window into the maternal structure with outstretched limbs.[14]

The Feminist Art Program [edit]

Subsequently, she was able to establish the Feminist Art Plan at the California Plant of the Arts, in Valencia with Judy Chicago. The program set up out to address the problems in the arts from an institutional position and focused on the expansion of a female person environs in Downtown, Fifty.A. In Womanhouse women were able to turn their invested creativity in rewarding their families with supportive environments toward themselves by allowing their fantasies to take over all rooms.[ii] They wanted the creation of art to be less of a private, introspective risk and more of a public process through consciousness raising sessions, personal confessions and technical training.[16] "('House') became the repository of female person fantasy and womanly dreams". Schapiro participated in the Womanhouse exhibition in 1972. Schapiro's smaller piece inside Womanhouse, called "Dollhouse", was constructed using various scrap pieces to create all the furniture and accessories in the house. Each room signified a particular role a woman plays in lodge and depicted the conflicts betwixt them.[17]

Feminist Art [edit]

Schapiro's work from the 1970s onwards consists primarily of collages assembled from fabrics, which she called "femmages". In the early seventies, succeeding Schapiro'due south collaboration in Womanhouse, she fabricated her first fabric collages in her studio in Los Angeles, which looked much like a room in a house. From the male technological globe of computers Schapiro moved into a woman'southward busy house. In this dwelling-like studio, Schapiro monumentalized her fabric cabinet and its significance for women, in a number of large femmages, including A Cabinet for All Seasons. This was her poetic version of the representation of continuous changes and repetitions in all women'south bodies and lives.[2] In her definition of femmage, Schapiro wrote that the style, which simultaneously recalls quilting and Cubism, has a "woman-life context" and that information technology "celebrates a private or public event." Equally Schapiro traveled the United States giving lectures, she would ask the women she met for a gift. These souvenirs would be used in her collage like paintings. Schapiro too did collaborative fine art projects, like her series of etchings Anonymous was a Adult female from 1977. She was able to produce the serial with a grouping of 9 women studio-fine art graduates from the University of Oregon. Each print is an impression made from an untransformed doily that was placed in soft footing on a zinc plate, then etched and printed.[2]

Her 1977-1978 essay Waste Not Want Not: An Inquiry into What Women Saved and Assembled – FEMMAGE (written with Melissa Meyer) describes femmage as the activities of collage, aggregation, découpage and photomontage practised past women using "traditional women's techniques – sewing, piercing, hooking, cutting, appliquéing, cooking and the like …"[18]

After 1975, Schapiro returned to New York and with what she fabricated after selling some paintings, she non only had a room only a studio of her own. Decoration and "collaboration," are key to her artwork and both play a significant role in her business firm as well as in her studio.[2] The studio became Schapiro'southward own room and at moments of great personal disharmonize, the simply connection with her creative self. Her various studios throughout the span of her career have reflected the changes in both the outer and the inner realities of her life. They take expressed her changing self-conceptions in accord with or in against society, which keeps gender roles dissever.[2] Schapiro's studios take also become metaphors for her artistic work, besides equally spaces in which she could live her life and fulfill her dreams as well.[ii]

Her image is included in the iconic 1972 affiche Some Living American Women Artists by Mary Beth Edelson.[19]

Collaborations and Identity [edit]

In the process of taking on different projects, Schapiro's studio expanded and somewhen became portable, post-obit her as she traveled from identify to identify. It was during the same time of her Oregon collaborative project with the nine women that Schapiro also created her first "Collaboration Series" with women artists of the by. This series combined reproductions of the piece of work of Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot with colorful and sensuous material borders in patterns inspired by quilts.[2] In Mary Cassatt and Me, Schapiro overlapped her own mental prototype of her mother with Cassatt'southward maternal platonic–her mother reading a paper.[two]

In the 1990s Schapiro began exploring her Jewish identity further in her painting. Her painting My History (1997) she used the same structure every bit the Business firm projection and built rooms of different memories surrounding her Jewish heritage. Her most explicit Jewish-themed statement in art was Four Matriarchs, stained glass windows portraying the biblical heroines Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah. This was a colorful piece combining identity symbology and her older domesticated art to create the true vision of what high fine art meant to the public. Mother Russia (1994), was a fan piece made by Schapiro that drew from her family unit'south Russian background. She depicts the powerful women from Russia each on a row of the hand held fan with a hat and a veil. She added pieces from each artist piece of work in her "collaborative" style to bring together them as revolutionary women and give hidden figures praise. Her background in both the Russian and Jewish culture have very much attributed to what Schapiro's collection of work represents. The foundation and collective use of patterns and colors describe Miriam'south work and allow us to see her civilization and female phonation.[14]

She was interviewed for the 2010 film !Women Art Revolution.[20]

Schapiro's works are held in numerous museum collections including the Smithsonian American Art Museum,[21] [22] Jewish Museum (New York),[23] the National Gallery of Art,[24] the Museum of Modern Art,[25] and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.[26] Her awards include the Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Achievement from the Higher Art Association[27] and a 1987 Guggenheim Fellowship.[28] Miriam Schapiro'southward estate is represented exclusively past Eric Firestone Gallery.

Awards and honors [edit]

- 1982: Skowhegan Medal for Collage[29]

- 1983: Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts, College of Wooster, Wooster, OH

- 1987: Guggenheim Fellowship for Fine Arts in US and Canada

- 1988: Honors Honour, The Women's Caucus for Fine art

- 1989: Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts, California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, CA

- 1992: Honors Award, National Association of Schools of Fine art and Pattern

- 1994: Honors Honor, New York State NARAL

- 1994: Honorary Doctorate Degree, Minneapolis and Pattern, Minneapolis, MN

- 1994: Honorary Doctorate Degree, Lawrence University, Appleton, WI

- 2002: Lifetime Accomplishment Award, Women's Caucus for Fine art

List of major works [edit]

- (1963) Shrines Grayness Art Gallery[30]

- (1968) Large Ox No. one Brooklyn Museum[31]

- (1972) Womanhouse

- (1972) Dollhouse, with Sherry Brody, Smithsonian American Art Museum[22]

- (1972) Lady Genji's Maze

- (1978) Connexion [32]

- (1983) Wonderland Smithsonian American Art Museum [21]

- (1990) Conservatory (Frida and Me) [33]

See besides [edit]

- Feminist fine art movement in the U.s.a.

- Feminist Art Program

- Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics

- Heresies Collective

- New York Feminist Fine art Plant

References [edit]

- ^ Cotter, Holland (2008-01-fifteen), "Scaling a Minimalist Wall With Bright, Shiny Colors", New York Times , retrieved 2009-09-12

- ^ a b c d due east f g h i j thou l k n Gouma-Peterson, Thalia (1999). Miriam Schapiro: Shaping the Fragments of Art and Life . New York: Harry N. Abrams Publishers. pp. 92.

- ^ Stein, Linda (1998). "Miriam Schapiro: Woman-Warrior with Lace". Fiberarts (24): 35–40.

- ^ a b Avital H. Bloch, Lauri Umansky, Impossible to Hold: Women and Culture in the 1960s, NYU Press, 2005, p319. ISBN 0-8147-9910-8

- ^ a b Ficpatrik, Milja. "Miriam Schapiro". Widewalls.

- ^ Salus, Carol (2009). "MIRIAM SCHAPIRO". Jewish Women's Archive.

- ^ Leffingwell, Edward (September 2006). "Schapiro's Material Girls A mini-retrospective of Miriam Schapiro's piece of work over the last 30 years on the theme of dolls and dancers included fabrics and images from an abundance of sources". Art in America. 94 (8): 130–133 – via Art & Compages.

- ^ Gouma-Peterson, Thalia. Miriam Schapiro: An Fine art of Becoming. American Art 11.1 (1997) : 10-45.

- ^ a b Gouma-Peterson, Thalia (1999). Miriam Schapiro: Shaping the Fragments of Art and Life. New York: Harry N. Abrams. p. 22.

- ^ "Remembering Miriam Schapiro (1923–2015)". 22 June 2015.

- ^ Grimes, William (25 June 2015). "Miriam Schapiro, 91, a Feminist Artist Who Harnessed Arts and crafts and Design, Dies". The New York Times.

- ^ Richmond, Susan (2004). "Gainesville, Georgia". Art Papers. 28 (4): 42–43.

- ^ Notebooks, Diaries and Sketchbooks. Miriam Schapiro Papers. MC 1411. Special Collections and Academy Archives, Rutgers University Libraries.

- ^ a b c d Yassin, Robert (1999). Miriam Schapiro Works on Paper a Thirty Yr Retrospective. Tucson, Arizona: Tucson Museum of Art. pp. 7–13.

- ^ Braude, Norma (2015). "Miriam Schapiro (1923-2015)". American Art. 29 (3): 132–135. doi:10.1086/684924. S2CID 191982290.

- ^ Arnason, H.H.; Mansfield, East.C. History of Modernistic Art. Prentice Hall. 2010. pp604. ISBN 0-205-67367-eight

- ^ 3.Schapiro, Miriam. The Didactics of Women as Artists: Project Womanhouse. Art Journal 31.three (1972) : 268-270.

- ^ Kristine Stiles, Peter Selz, Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists' Writings, University of California Press, 1996, pp151-iv. ISBN 0-520-20253-eight

- ^ "Some Living American Women Artists/Final Supper". Smithsonian American Art Museum . Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Betimes 2018

- ^ a b "Wonderland, Miriam Schapiro". Smithsonian American Art Museum . Retrieved 2018-07-10 .

- ^ a b "Dollhouse, Miriam Schapiro". Smithsonian American Art Museum . Retrieved 2018-07-x .

- ^ "Miriam Schapiro". The Jewish Museum . Retrieved 2018-07-10 .

- ^ "Miriam Schapiro". The National Gallery of Art . Retrieved 2018-07-10 .

- ^ "Miriam Schapiro". Museum of Modern Art . Retrieved 2018-07-10 .

- ^ "Miriam Schapiro". PAFA. Archived from the original on 2018-07-10. Retrieved 2018-07-x .

- ^ Miriam Schapiro, feminist artist and Pattern & Ornament painter, received the distinguished artist honor for lifetime achievement - People - Cursory Commodity, Art in America, August 2002.

- ^ "Miriam Schapiro". Fellows. John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Archived from the original on Jan 4, 2013. Retrieved Oct 19, 2012.

- ^ "Mairiam Schapiro Awards Folio" (PDF). Mariam Schapiro. Retrieved eleven Feb 2014.

- ^ http://www.nyu.edu/greyart/exhibits/nycool/27shapiro.html

- ^ Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Fine art: The Dinner Party. Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved on 2014-01-24.

- ^ "Connection, Miriam Schapiro". WikiArt . Retrieved 2018-07-ten .

- ^ "Conservatory, Miriam Schapiro". WikiArt . Retrieved 2018-07-10 .

- Anon (2018). "Artist, Curator & Critic Interviews". !Women Art Revolution - Spotlight at Stanford. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

Books [edit]

- Gouma-Peterson, Thalia, and Miriam Schapiro. Miriam Schapiro: Shaping the Fragments of Art and Life. New York: Harry North. Abrams Publishers, 1999. Print.

- Herskovic, Marika New York School Abstract Expressionists Artists Pick by Artists, (New York School Press, 2000.) ISBN 0-9677994-0-6

- Schapiro, Miriam, and Thalia Gouma-Peterson. Miriam Schapiro, a retrospective, 1953 - 1980: Wooster, OH: n.p., 1980. Print.

- Schapiro, Miriam, Robert A. Yassin, and Paul Brach. Miriam Schapiro: works on paper: a xxx-year retrospective. Tucson, AZ: Tucson Museum of Art, 1999. Print.

External links [edit]

- Archives of American Art interview

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miriam_Schapiro